As in Part I, links to Wikipedia articles often take you to the French version because they're often more complete. There's usually a link to the English translation in the left-hand column.

Montréal, Friday 4 June

We berthed at Montréal’s Iberville Cruise Terminal at 8 am to cloudy skies and the prospect of rain in the afternoon. We had no excursions planned so we decided to walk around the city. Leaving the terminal, we turned right into rue de la Commune and soon reached Pointe à Callière. We didn’t realise it at the time, but we were at the the birthplace of Montréal's forerunner, Ville-Marie.

As we rounded it into Place d'Youville, we hardly noticed the Museum of Archaeology and History let alone photographed it. And we certainly didn't see that, in front of the museum there's a black bollard that presumably marks the spot where the birth took place. In this and many ensuing cases, where I had neglected to take a photograph, a Wikipedia subscriber, Jean Gagnon, had done so. I've used his shots liberally to fill in the gaps. Here's his photo of the museum. If you enlarge it, you can just see the bollard in the centre:

Musée d'archéologie et d'histoire de Montréal, Pointe à Callière

(Jean Gagnon, Wikimedia). Rue de la Commune is on the left

and Place'd'Youville and Place Royale are on the right.

(Jean Gagnon, Wikimedia). Rue de la Commune is on the left

and Place'd'Youville and Place Royale are on the right.

Incidentally, it's interesting to compare the museum building with the 1992 building it replaced. Its architect, Dan Hanganu, has clearly taken some account of the form and spirit of the original building.

Royal Insurance Company c1875

(William Notman via Wikimédia)

The Royal Insurance Building served as Montreal's Customs house between 1871 and 1917. However, it caught fire in 1947 and was demolished a few years later.

At Place Royale opposite the museum is Montreal's original Customs House. We missed that too. Fortunately, Jean didn't, so here's his photograph of that building:

The Customs House at Place Royale (Jean Gagnon, Wikimedia)

On returning home to Bristol I studied a great many historical documents in an attempt to to check on the validity of the claim that Pointe à Callière was the birthplace of Montréal. But I soon found that I had waded into a quagmire of uncertainty. Even, François Dollier de Casson, the first known chronicler of the early history of Ville-Marie, admits to being less than certain about the timing of events. He arrived there in 1667, 15 years after its foundation and became the third Superior of the Seminary of Saint Sulpice, the religious society that played such a large part in the early history of Montréal. His 118-page memoir, Histoire du Montréal, had to wait until 1871 for publication. On the first page he warns his readers that there will be “a few slight errors” in the timing of events. So what hope have I? Nevertheless, I've tried to present the most likely train of events.

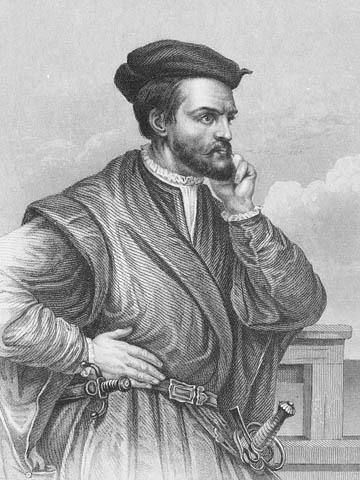

After Columbus’s voyages to America during the decade following 1492, Spain’s American empire expanded rapidly. François I (1494-1547), King of France from 1515 until his death, was sufficiently alarmed that he determined to acquire an empire of his own. The man he chose for the task of realising his dreams was Jacques Cartier (1491-1557), a Breton from Saint-Malo. The King charged Cartier with three main tasks: to set up a French colony, to look for gold and to seek a northwest passage to the orient.

Jacques Cartier (Dbenbenn, Wikimedia)

Cartier set sail for the Americas in April 1534 only two years after Brittany had been united with France in the Edict of Union. Less in a month later he was exploring present-day Newfoundland. That was over 60 years before King James I granted a charter to the London-based Virginia Company to establish the first English settlement in America.

During his voyage Cartier explored the land around what is now known as the Gulf of St Lawrence but did not attempt to sail up the St Lawrence River itself. However, during a second voyage in 1535 he sailed about six hundred miles up river and there encountered a 30-mile long island. It wasn't until much later that it became known as the Island of Montréal but, to keep things simple, I'm giving it that title from the outset. On exploring it, he found that it was inhabited by an indigenous people of a tribe called Iroquoian. About 3000 of them lived in a fortified village called Hochelaga meaning “beaver dam”. Less than a mile from the village was a mountain with three peaks. Cartier called Mont Réal. Réal is not a modern French word but, in Middle French, it meant Royal as it does in present-day Spanish. Cartier was of course naming the mountain in honour of his Royal patron, François.

Jacques Cartier's second voyage (Yannick Loukianoff after H.P. Biggar)

Cartier returned to the St Lawrence River in 1541 bringing with him, colonists and convicts. He landed near

present-day Québec City and a colony was established at Cap-Rouge in present-day Québec City. It was near an

existing native village that he called Stadacona. There are various reports as to what he did next. It seems likely

that he explored the area around Saguenay seeking gold with little or no success. However, what is on record in his

Journal is that on the 7th of September 1541 he set sail from Cap-Rouge for Hochelaga on the island he had visited

six years earlier. He recorded that he reached the island on the 11th but, at that point, his journal ends. There is no

further mention of Hochelaga. Maybe the village had been deserted on account of the land becoming exhausted. Such

population movement was quite common among North American indigenous tribes at the time. Cartier didn’t spend long on the island

but rather returned to Cap Rouge in present-day Québec City where he spent the winter. He returned to France in the summer

of 1542 and lived out the rest of his life in and around his hometown of Saint-Malo.

During the ensuing years the settlements in the areas around Cap-Rouge and Saguenay burgeoned and the region was soon officially declared to be la colonie de Nouvelle- France. However, it wasn’t until 1611 that an attempt was made to extend the colony as far upstream as the Island of Montréal. The man in charge of that undertaking was Samuel de Champlain (c1570-1635), the so-called “Father of new France”.

Samuel de Champlain (Charvex, Wikimedia)

In preparation for the founding of a trading post, de Champlain cleared a site at the mouth of Flueve Saint-Pierre. It was Champlain who gave the name Place-Royale to his landing place. Fleuve Saint-Pierre is at the bottom left-hand corner of the 1758 map below and is given its English name of St Peter’s River. You can see a zoomable version of the map here. Neither Place-Royal nor Pointe de Callière is marked on the map. However, the house of Monsieur de Callière at the mouth of the river is shown. Louis Hector de Callière (1648-1703), by the way, was the third Governor of Ville-Marie.

Carte de la Ville-Marie. 1758 (Anonomous, The McCord Museum )

As shown in the various maps that are accessible through the links below, the courses of the waterways of the south-west of the Island of Montreal have changed over the years. Bear in mind that maps of Montréal and its island – even modern ones – tend to be aligned with southwest on the left and northeast on the right. That means north is often 45° clockwise from vertical and sometimes even more. The above map of Ville-Marie in is an example.

To view zoomable maps of Island of Montreal view the 1892 map from the McGill Library and the 2012 map from the Réseau cyclable de Montréal.

To see how the Little Saint-Pierre River disappeared over the years click on Cartes de Montréal, Following Rivière St. Pierre and Base de données – Les Premiers Montréalais.

To view hundreds of maps and other images click on Montréal Archives.

The first map in the Following Rivière St. Pierre article shows the network as it was in 1739. It would have been substantially the same in 1642. Streams run south-westwards and north-eastwards from Lac Saint- Pierre. The main course of the latter stream soon turns in a south-easterly direction but the lesser course flows roughly north. Though you possibly can’t read it, it's named as:

Un petit canal que Messieurs du Séminaire ont fait pour donner de l’eau au moulin marqué M

(A small channel that the men of the Seminary made to provide water to the mill marked M)

As shown in the 1892 map, during the 19th century the Lachine Canal and the City of Montréal Aqueduct were built. The third map in the Following Rivière St. Pierre article shows how the Lachine Canal follows roughly the course of the original Saint-Pierre and Petit Saint-Pierre rivers.

Returning to the early 17th century, Champlain’s attempts to establish a trading post were unsuccessful and the

colonisation of the Island of Montréal had to wait another 30 years. Then, happenings crucial to the development Montréal

took place in Paris. At the heart of the Saint-Germain-des-Prés quarter of that city stands the 13th century Church of Saint-Sulpice.

It's an impressive building only exceeded in size amongst Parisian churches by Notre-Dame:

Eglise Saint-Sulpice Saint-Jermaine-des-Prés (Mbzt, Wikimedia)

The monument features four bishops of the reign of Louis XIV

The monument features four bishops of the reign of Louis XIV

It was at the Church of Saint-Sulpice in December 1641 that the Society of Saint Sulpice was founded by its parish priest, Jean-Jacques Olier. Although Olier’s primary aim in founding the Society was to educate an ignorant and decadent French priesthood, he was also greatly interested in developments in New France. He was anxious to extend missionary activity there. And he had heard reports of a man called Jérôme Le Royer de la Dauversière who had similar aspirations. Dauversière, was a wealthy but enlightened nobleman from La Flèche, 150 miles south-west of Paris. The two men met and immediately formed a bond that was to prove lifelong. They determined that the French colony should be established in the Island of Montréal and, to that end they formed the Société de Notre-Dame de Montréal pour la conversion des Sauvages de la Nouvelle-France (Society of Notre-Dame). They recruited a forty-strong party of would-be colonists– mainly men but with five or ten women. An important member of the party was one Paul de Chomedey, sieur de Maisonneuve who was to be appointed the first Governor of Montréal. They set sail for Canada in June 1641 and over-wintered in Cap-Rouge. Whilst they were there, Olier and Dauversière decided that the island should be placed within the patrimony of the Virgin Mary. They therefore called the new settlement Ville-Marie, a name that stuck for over a hundred years before it became known as Montréal.

In early May 1842 the would-be colonists left Cap-Rouge for the Ile de Montréal arriving there on the 18th. They landed, it is said, at Place Royale. The day before they arrived Charles de Montmagny, the first Governor of New France, had granted the Society of Notre-Dame possession of the Island of Montréal.

|

|

During the colonists' first year on the island, Maisonneuve organised the building of a Fort, a chapel a cemetery and the first dwelling places. The Iroquoians had been friendly towards Cartier when he first visited the island but they had been much less well disposed towards Champlain. Maisonneuve therefore took the precaution of having the settlement surrounded by a picket fence. In fact, the Iroquoians didn't become aware of the settlement until June 1643 but, after that – and for the next quarter of a century – they continually harassed the colonists.

During the early years, the Jesuits had worked with Olier to fulfill his aim to provide missionaries service in the area round Ville-Marie. However, Olier suffered a stroke in February 1652. He placed his pastorate of Ville-Marieinto in the hands of Abbé de Bretonvilliers and returned to France. Olier lived another five years and, just before he died in 1657, he arranged for four priests from the Saint-Sulpice Seminary in Paris to establish a similar seminary in Ville-Marie. Some accounts say that he accompanied them, but that seems unlikely in view of his state of health. Henceforth the Seminary became the dominant religious force in and around Ville Marie. In 1663 temporal powers were added when the Society of Notre-Dame ceded the Seigneurie of Ville-Marie to the Seminary.

Maisonneuve's achievements would not have been possible without the constant support of Jérôme Le Royer de la Dauversière. Sometimes Dauversière would go to France and arrange for resources to be sent to Ville-Marie. Often these resources were financial but, when he died in November 1659, this once-wealthy man was close to bankruptcy.

François Dollier de Casson, who succeeded Bretonvilliers as Superière, was largely responsible for rationalising the parish of Notre-Dame and commissioning the building of a more substantial church in 1672:

L'Ancien Eglise Notre-Dame, Ville-Marie

(Histoire du Montréal, François Dollier de Casson)

François Dollier de Casson

(Wikimedia)

Back to the 21st-century!

We had emerged from the cruise terminal turned right along Rue de la Commune and sharp left at Point à Callière into Place d’Youville named after Saint Marguerite d'Youville, a Quebécoise widow who founded the religious order the Sisters of Charity of Montréal, known colloquially as the Grey Nuns. Place, of course, translates as square but the first hundred yards of Place d’Youville is a road rather than a square. Only after that does it broaden out into a small square called Place de la Grande-Paix de Montréal in the centre of which is an obelisk commemorating the pioneers of Montréal:

On each of the four faces at the base was a plaque. One of them (inset in the photograph) summarises the origins of the city as follows:

Le 18 May 1642

Près de cet obélisque entre le Fleuve et la Rivière qui coule sous la rue des commissaires à l’endroit appelé place royale par Champlain, le 18 Mai 1642 Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve jeta les fondements de la Ville de Montréal.

Il érigea les premières habitations, le fort, la chapelle, le cimetière

Qu’il referma dans une enceinte de Pieux

Le 13 Février 1644 Montréal avait été consacre à la Sainte-Vierge sous le nom de Ville-Marie

Le 13 Février 1644 Louise XIV lui accorda sa première charte civique

Le 26 Mars 1644 Chomedey de Maisonneuve en fut nomme premier gouverneur particulier.

Près de cet obélisque entre le Fleuve et la Rivière qui coule sous la rue des commissaires à l’endroit appelé place royale par Champlain, le 18 Mai 1642 Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve jeta les fondements de la Ville de Montréal.

Il érigea les premières habitations, le fort, la chapelle, le cimetière

Qu’il referma dans une enceinte de Pieux

Le 13 Février 1644 Montréal avait été consacre à la Sainte-Vierge sous le nom de Ville-Marie

Le 13 Février 1644 Louise XIV lui accorda sa première charte civique

Le 26 Mars 1644 Chomedey de Maisonneuve en fut nomme premier gouverneur particulier.

Which, freely translated, is:

18 May 1642

Near this Obelisk between the River and the stream that flows under Rue des Commissaires to the place that Champlain called Place Royal, on 18 May 1642, Paul Chomedey de Maisonneuve laid the foundations of the City of Montréal.

He erected the first homes, fort, Chapel and cemetery that he enclosed with a picket fence.

On February 13 1644, Montreal was dedicated to the Virgin Mary with the name Ville-Marie.

On February 13 1644, Louise XIV granted its first civic charter.

On 26 March 1644, Chomedey de Maisonneuve was named first local governor.

The obelisk was designed by J.A.U. Ubald and erected in 1892 to celebrate the 250th anniversary of the foundation of the City.

Further along Place d’Youville are the Youville Stables (see English translation but without the plan of the site):

Partie de les écuries d'Youville

The Grey Nuns, the original owners, retained ownership until the 1960s by, by then, the buildings had become run down. In 1967 they were redeveloped as offices shops and restaurants. The most popular venue in the complex is a steakhouse known as Gibby's. For a history of the complex (in French) see Entrance to Youville Stables.

Centre d'histoire de Montréal

The architects were Joseph Perrault (1866-1923) and Simon Lesage. The building's use as a history centre dates from the 1970s.

Edifice des Duanes, 105 rue McGill

(Jean Gagnon, Wikimedia)

Grand Trunk Railway Office, McGill Street in 1906

(photograph from the McCord Museum, Montréal)

We walked a short distance up McGill and then turned right into rue Saint-Paul. It’s the oldest thoroughfare in the city, but you wouldn’t think so – not from the end we were at any rate. Just like McGill, Saint-Paul is full of late Victorian and Edwardian buildings. We took the first left into rue rue Saint-Pierre and saw this building at its junction with rue des Récollets:

Victorian extravaganza: 451 rue Saint-Pierre

It was built in 1865-1866 to the design of Cyrus Pole Thomas and his son, William Tutin Thomas. They were responsible for quite a number of buildings in Montréal. In his book Montreal in Evolution, the respected Montréalien architect, academic and writer Jean-Claude Marsan is scathing about both this building and the British Empire Building which we passed soon after. On page 241 he writes:

The streets of the old town are littered with nineteenth-century commercial buildings whose facades are an orgy of

decoration, the unfortunate result of various blends of styles, predominantly Italian. In such instances, structural

considerations as well as climatic conditions have been ignored: only the picturesqueness of the "attire" matters.

Three contiguous buildings located at 38-60 Notre-Dame Street West provide a good example of this often heavily

pretentious type; another is on the southwest corner of Notre-Dame and Saint-Francois-Xavier Streets, appropriately

named the British Empire Building.

Other structures display extremely superficial textures. Many a Montrealer must have been struck by the look of the facade of a building located at 157 Saint-Paul Street West, across from John Osten's serious Customs House; it is covered with faked rustic stones whose motifs change with every floor. However, when it comes to decorative extravaganza, the building located at 451-57 on Saint-Pierre Street is unsurpassed. Its overloaded facade defies description: it may rival that of the most exalted Venetian palace. (my italics).

Other structures display extremely superficial textures. Many a Montrealer must have been struck by the look of the facade of a building located at 157 Saint-Paul Street West, across from John Osten's serious Customs House; it is covered with faked rustic stones whose motifs change with every floor. However, when it comes to decorative extravaganza, the building located at 451-57 on Saint-Pierre Street is unsurpassed. Its overloaded facade defies description: it may rival that of the most exalted Venetian palace. (my italics).

After looking at the derided number 451 returned back down rue Saint-Pierre the short way to rue du-Saint-Sacrament where we turn left. Soon we saw the old Board of Trade Building on our right:

The former Board of Trade Building

Located at 300 rue du Saint-Sacrament, this is the second building to be built for Montreal’s Board of Trade on this site. The first dated from 1891 and was designed by a team of three Bostonian architects: George Foster Shepley (1860–1903), Charles Hercules Rutan (1851–1914), and Charles Allerton Coolidge (1858–1936). That building was destroyed by fire in January 1901 and was rebuilt in 1903 on the same foundations but with a different design, this time by the David Robertson Brown partnership.

At the end of rue du Saint Sacrament we saw the former Montréal Telegraph Building on our right before turning left into rue Saint Francois-Xavier:

The former Montréal Telegraph Building

The building dates from 1873 and was designed by Hopkins and Wily. John William Hopkins (1825-1905) was a Liverpudlian and Daniel Berkeley (1832-1889), was native of the Jersey. Their most notable realisation was the Art Gallery of the Art Association of Montréal.

Immediately after that, at 453-457 on our right, we saw Stock Exchange building:

Édifice de la Bourse de Montréal

It was built to the design of the American architect George B Post who was also responsible for the construction of the New York stock exchange building. The Montréal architects Edward and William Maxwell were also involved in the construction of the building.

100 yards along rue Saint-François-Xavier after the stock exchange building we reached rue Notre Dame. On the corner on our left we saw the British Empire Building, the other edifice that Jean-Claude Marsan had been scathing about on page 241 of his book:

The British Empire Building

By now we were suffering from a surfeit of Victoriana and were glad to see some older buildings in front of us. In fact the one on our right – the Old Seminary of Saint-Sulpice – is the oldest surviving building in Montréal:

Vieux Séminaire de Saint-Sulpice

Dating from between 1684 and 1687, it was – and still remains – the Montréal home of the priests and other members of the Society of Saint-Sulpice. The history of the Society is closely linked to that of the Basilica of Notre Dame which was the building we saw next:

Basilique Notre-Dame de Montréal

Whilst Montreal’s Notre-Dame owes its spiritual heritage to the Paris Church of St Sulpice,

its architectural antecedence lies at least partly in a cathedral with which it shares a dedicatee. It's not

far away from St Sulpice:

Notre Dame de Paris (Amandajm, Wikimedia)

West of the towers of each of these great ecclesiastical buildings lies a square of commensurate proportions – and each has a single monument. In the case of Notre Dame, Paris, a statue of Charlemagne stands in Place John Paul II. Place Saint Sulpice has a fountain above which four seated bishops face respectively north, east, south and west. The centrepiece of La Place d’Armes in Montréal is a statue of the city's founder, Paul de Chomedey, sieur de Maisonneuve:

Maisonneuve et Basilique Notre-Dame

Place d'Armes et Basilique Notre-Dame de Montréal

Montréal's Notre-Dame was designed by James O’Donnell, an Irish-American Anglican from New York, and the towers in particular are reminiscent of his earlier design for Christ Church, an Episcopal church in New York:

Christ Church, Anthony Street, New York

O'Donnell died in 1830 by which time, although the main body of the church was complete, some features – notably the towers – were yet to be added. It is said that he converted to Roman Catholicism on his deathbed in order that he could be buried in the crypt of the church that he had designed.

Towers designed by John Oster based on O'Donnell's original design were added later. One was built in 1841 and the other in 1843. At the time of its completion, Notre-Dame was the largest church in North America. It remained so for a further 50 years. Nowadays it's not even the largest church in Montréal – that honour belongs to Saint Joseph's oratory. Nevertheless, during his visit to the city in April 1982, Pope John Paul II saw fit to bestow Basilica status upon the church.

The original Notre Dame Church served as the Cathedral of the Diocese of Montréal from 1821 to 1822 but, although there are five cathedrals within the City of Montréal, the present Church of Notre-Dame has never been one of them. The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Montréal is administered from the Cathedral of Mary, Queen of the World in East Montréal. It also is a basilica, though a minor one.

Opposite the Basilica in Place d’Armes stands this building:

Édifice de la Banque de Montréal

Designed by John Wells (1789-1864), an English-born architect who had come to Montréal in about 1830, it was originally the head office of the Bank of Montreal.. It's interesting to compare the building with the former headquarters of the Commercial Bank of Scotland in Edinburgh designed by the Scottish architect, David Rhind:

'The Dome', Edinburgh – the former headquarters of the

Commercial Bank of Scotland (David Gray, Flickr)

The similarities are quite striking. Except that the relief carvings are different, the architrave and the six Corinthian columns are virtually identical even down to the cornices. Furthermore, both buildings have a dome. In fact the Edinburgh building is actually called The Dome. It's hard to avoid the conclusion that one design was inspired by the other and indeed one or two authorities – notably Wikipédia Français – assert that Wells was influenced by Rhind. But the trouble with that contention is that the two buildings were designed and constructed almost concurrently. Work on the design of the Edinburgh building started in 1843 and construction was complete in 1847, whereas the Montréal building was designed and built between 1845 and 1848. There is no doubt, however that both buildings were inspired by Greco-Roman architecture. Buildings with similar porticoes found all over the world include the Pantheon in Paris (modelled after the building of the same name in Rome), the Temple of Hephaestus and Athena in Athens and, in particular, the Temple of Concordia in Sicily. The latter building is shown in Evan Erickson’s photograph:

The Temple of Concordia, Sicily (Evan Erickson, Wikipedia)

Having said all that I still have a nagging feeling that Wells was familiar with Rhind's design.

The Bank of Montreal, founded in 1817, is the oldest banking group in Canada. However, as a result of the political instability in Québec Province, its head office was moved to Toronto in 1977. Until 1944, when the Bank of Canada became the only bank that was allowed to issue banknotes, a number of Canadian issued their own versions. The Bank of Montréal was one of the last to do so. Here's one of their five dollar notes:

A five dollar bank of Montréal note (Godot13, Wikimedia)

There are two quirky sculptures in Place d'Armes. Here's one of them:

On the plaque beneath it is written: "Le caniche francais et le carlin anglais – "The English Pug and the French Poodle". It's the work of the artist Mark A.J. Fortier and was made as the Atelier du Bronze Foundry.

We sat down for a while seats in the centre of the Place d'Armes watching the horse-drawn carriages go by before walking further hundred yards or so up rue Notre Dame. Just past McDonald's on the left was the new Palais de Justice, Montreal's courthouse. It's long and low at the front and high the rear. I didn't photograph it but Jean Gagnon did:

Palais de Justice (Jean Gagnon, Wikipédia)

It's Montreal's third courthouse. The second, known as the Ernest-Cormier Building, located at 100 Rue Notre Dame East, was built between 1922 and 1926 to a design by the architects Louis-Auguste Amos, Charles Jewett Saxe and Ernest Cormier. It currently houses the Québec Province Court of Appeal:

Édifice Ernest-Cormier

Further on the left, adjoining the new Palais de Justice, is Montreal's original courthouse:

Vieux Palais de Justice de Montréal

Located at 155 Rue Notre Dame East, it was Montreal's first courthouse. It was built between 1851 and 1857 to the design of architects John Ostell and Henri-Maurice Perraultand, and was subject to major modifications between 1890 and 1894. It is now known as Édifice Lucien- Saulnier and houses the city of Montréal municipal offices. In 2013 was renovated at a cost of C$50,000,000.

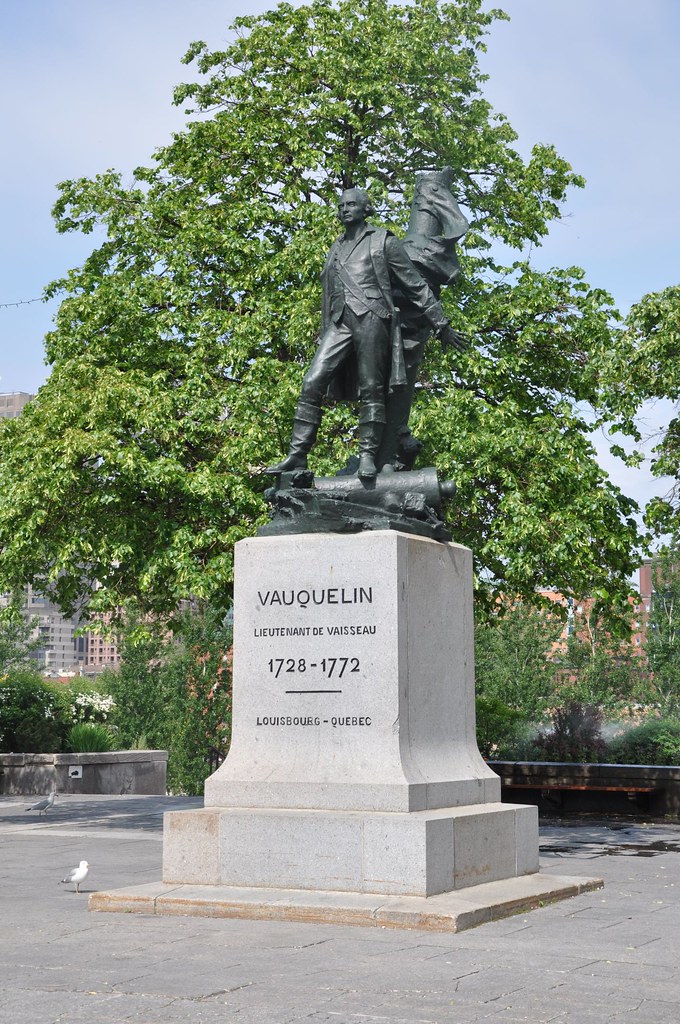

Beyond the old Palais de Justice, rue Notre Dame opens out into a large square called Place de la Dauversière with a smaller square called Place de Vauquelin on the left. The smallest pool contains a pool and a statue. You can see a bit of the pool in this photograph of the side of the old Palais de Justice:

Vieux Palais de Justice de Montréal

The next photograph shows more of Place Vauquelin with the statue beyond the pool:

Place Vauquelin

The statue is of the man after whom the square is named, Jean Vauquelin.

|

|

In the centre of Place de la Dauversière is a scaled-down version of the Nelson's Column in Trafalgar Square – a rather surprising monument to see in French Canada. It's interesting to compare Vauquelin with Nelson. Vauquelin (1728-1772) was a naval officer from Dieppe. He came to Canada in 1759 and fought a number of naval battles with the British along the St Lawrence River. He was captured by the British but they were so impressed with his bravery that they released him for return to France. Nelson, of course, was a British naval officer who fought against the French during the Napoleonic wars. I'm surprised that his monument has managed to survive in Montréal. Perhaps the fact that the plaque at the base of the column celebrates Nelson's victory at Copenhagen – albeit written in French – rather than at Trafalgar has saved his column from attack by the Québec Liberation Front. Here's a translation:

On the 2nd of April 1801 a British fleet of 10 sail of the line and 8 ships of 50 guns under the immediate command

of the Right Honourable Vice Admiral Lord Viscount Nelson Duke of Bronte attacked the Danish line moored for the

defence of Copenhagen consisting of six sail of the line and 11 large ship batteries besides bomb and gun vessels

supported by the ground and land batteries when, after a severe contest of 4 hours, the whole line of defence was

sunk, taken or destroyed without the loss of a British ship.

Dominating Place de la Dauversière is Montreal's Town Hall:

Hôtel de Ville de Montréal

It was built

between 1872 and 1878 to the design of architects Henri-Morris Perrault and Alexander Cowper Hutchison. It is

thought to be one of the best examples of the Second Empire Style in Canada.

Opposite the City Hall is Château Ramezay, now a historical museum and portrait gallery. It was built in 1705 to a design of Paul Tessier as the residence of Claude de Ramezay (1659-1724), Governor of Montréal from 1714-1716:

Musée Château Ramezay

We didn't visit the museum but we did see the Jardin du Gouverneur behind it. It's a small garden open to the public which is – in the words of the official tourist guide – “a typically delightful 18th century urban retreat”:

Le Jardin du Gouverneur

(Musée Château Ramezay)

Beside the museum, in another small public garden within Place de la Dauversière, we saw a statue of Jean Drapeau (1916-1999), a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as mayor of Montréal from 1954 to 1957.

Statue of Jean Drapeau

Southeast of Place de la Dauversière is Place Jacques-Cartier, a wide, semi-pedestrianised road named after the first European to reach the Island of Montréal. Here's Jean Gagnon's shot of it looking up towards the town hall from rue Saint-Paul Est:

Place Jacques Cartier (Jean Gagnon, Wikipédia)

For some reason we didn’t walk down it but instead continued a couple of blocks along rue Notre-Dame. When we reached rue Saint-Claude we looked right and saw this little church at the bottom of the road:

Chapelle Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours

viewed from rue Saint-Claude

The church was the Chapel Our Lady of Good Help, located in rue Saint-Paul East, a road that runs roughly parallel to rue Notre-Dame but nearer the river. It turned out to be one of the oldest churches in Montréal. Nonetheless it was not the first to be built on the site. That was a small chapel built between c1655 and c1675 at the behest of Marguerite Bourgeoys, the young girl who accompanied Olier, Dauversière and Maisonneuve when they first sailed to Ville-Marie. Later she became a nun and founded the congregation of Notre-Dame.

The destruction by fire of the first chapel in 1754 prompted the construction of the present church between 1771 in 1773. Although it’s known that Joseph Morin, a stonemason, and Pierre Raza, a carpenter, were largely responsible for the building of the chapel the architect is unknown. The importance of this this small chapel and the area in which it is located is witnessed by the fact that a 147-page book has been written on the subject. Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours: une chapelle et son quartier by Patricia Simpson and Louise Pothier was published in 2001.

Chapelle Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours

viewed from rue Saint-Paul Est

Intérieur du Chapelle Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours

South-west of the chapel on the same side of the road we saw a long domed building:

Marché Bonsecours

It was the Bonsecours Market at 350 Rue Saint Paul East. It dates from 1847 and was designed in the Palladian style by the British architect William Footner. The name was taken from the chapel itself.

For just one year – 1849 – the building was used by the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada. The Province in question existed from 1841 to 1867. Subsequently the British North America Act of 1867 divided the Province of Canada into the provinces of Ontario and Quebec with each province having its own Legislative Assembly, as well as representation in the Parliament of Canada. That arrangement has survived until the present day.

Terrasses Bonsecours (Jean Gagnon, Wikimedia)

We were in Montréal on Friday 5 June 2015. It was the prelude to the Montréal Grand Prix weekend. The chequered banners on the main entrance to Marché Bonsecours proclaimed the forthcoming event. I’m going on memory now, but I believe that some Black Watch passengers had taken up the option to attend the Grand Prix and it had cost them about £300 each. Presumably, after the two-day event, they would have been taken by coach to the next port of call, Québec, where the ship was staying for two nights. all I can say is, if that’s true, then bully for them! I can think of lots of better ways of spending £300 – and they don't involve missing the opportunity to visit Québec City.

The Canadian Grand Prix has been held in Canada since 1961 and has been part of the Formula One championship since 1967. The race has been held at the Circuit Gilles Villeneuve in Montréal since 1982. Villeneuve sounds as if it is a word drawn from the early history of Montréal taking Ville from Ville-Marie and neuve from Maisonneuve. In fact it’s nothing of the kind.! The name is in honour of the Canadian racing driver Gilles Villeneuve, born in 1950, who died during a qualifying round for the 1982 Belgian Grand Prix. The track is on an island on the other side of the St Lawrence virtually opposite the Marché Bonsecours.

Circuit Gilles Villeneuve, (Radio Canada)

The result of the 2015 Grand Prix was a triumph for Mercedes. Lewis Hamilton was first and Nico Rosberg was second.

Having tarried a while at Bonsecours Marché, we back-tracked along Rue Saint-Paul to rue Berri into which we turned left. Just before reaching rue Notre-Dame, rue Berri splits briefly into two. Vehicles pass under rue Notre-Dame whereas pedestrians walk up a slope to the level of rue Notre-Dame. Jean Gagnon to the rescue again:

Intersection des rues Berri et Notre-Dame regardé sud

(Jean Gagnon, Wikipédia français)

Jean's View is looking in the opposite direction to that which we walked. At the upper level, at the junction of the two roads, we passed this building on the left:

Maison Sir-George-Etienne-Cartier

It's the Sir George-Étienne Cartier National Historic Centre which celebrates the lives of George-Etienne-Cartier and his family. The building dates from 1837 and the Cartier family acquired it in 1848. Although Sir George's father, grandfather, and great-grandfather all bore the first name of Jacques, George-Étienne Cartier was not a descendant of the Jacques Cartier who was the first European to visit the Island of Montréal back in 1535.

Further along rue Berri we saw this building on the right:

Édifice Jacques-Viger, Montréal

It's at the junction of rue Berri with rue Saint-Antoine and is known as the Jacques-Viger Building. For a moment I thought we were in Québec City already! But that was not so surprising when I found out that the architect, the very prolific American Bruce Price, also designed the similar-looking but much grander Chateau Frontenac in Québec City.

The Jacques Viger Building dates from 1898 and was originally an integrated station and hotel – the first of that type in Canada. From 1939 until 1950 the it was occupied by the Canadian Government. Later it was used by the municipality of Montréal but, from 2003 until recently, it was disused. Happily, In a harp back to its original purpose, it's become a college supporting the hotel industry.

From the Jacques Viger building we continued along rue Berri to rue Viger. Without realising it we were passing over the Ville-Marie Tunnel that was opened to traffic in 1985 to take Autoroute Ville-Marie through old Montréal. Either side of us were green areas which we discovered later were part of Place Viger – at least that’s what it’s called in this wonderful 1942 pictorial map that was of course made years before the tunnel was built. Amazingly, Google maps seem to have got it right. They call it Place Viger as well! We were pretty tired so we went into a green part of Place Viger that we saw on the right. From one of the seats we could see this impressive view of the Jacques Viger building:

Édifice Jacques-Viger viewed from Place Viger

As we emerged from Place Viger we saw the Gilles-Hocquart Building on the opposite side of the road:

Édifice Gilles-Hocquart

It's part of a complex comprising three adjoining buildings. The first is Marie-Hélène-Jodoin House, it was built in 1871. The building we were looking at was the second. It dates from 1910 and was designed by The Québecois architect, Louis-Zéphirin Gaultier (1842-1922). It once housed the HEC Montréal School but is now occupied by BAnQ Vieux-Montréal, a museum and archive centre. The the latest of the adjoining buildings to be built was a modern annexe.

Close to the Gilles-Hocquart Building on the same side of the road stands the French Union Building:

Édifice Union Francaise

It was built in 1867 in the Second Empire Style by the financier and shipowner Jacques-Félix Sincennes.

The French Union dates from 1 June 1886. At that time its main task was to organize a traditional ball on the 14th of July of each year. However, on the acquisition of this building in 1908, it focused on a social mission and became a shelter to house French needy. Over the years and particularly during the two world wars and the 1930 financial crisis, the French Union adapted to meet the needs of the community. In the period before the Quebec and Canadian governments introduced welfare measures, the Union gave home help and medical consultations to the needy. Later years saw the introduction of evening classes, help in seeking jobs and other services to support French immigrants in adapting to the Quebec environment and solve problems personal, marital or family.

The French Union also hosted several French organizations and institutions such as the Consulate General of France.

We were at the corner of Avenue Viger Est and rue Berri and it was time to return to the ship for lunch so we walked south-west along Avenue Viger Est. After just over a hundred yards we came to this strange spectacle at the junction with rue Saint-Denis:

Réplique de l'Église Saint Sauveur

When I got in Bristol I unearthed the story behind the building. In 1865 a Gothic revival church, was built for the Anglican community in Montréal. It was known as Trinity Church and the architects were Frederick Lawford, and James Nelson [1]. Though Lawford was born in Antwerp in 1821, his parents were English and he was brought up in London. He died the year after the church was completed [2] [3]. Nelson was born in Belfast in 1930 and was brought to Canada by his parents in 1840. In 1894 he was elected president of the Province of Québec Association of Architects. He died in 1919. [3]

In the course of time, the church became a refuge of piety for Canadian soldiers who lived in the surrounding garrisons. Then, in 1909, the parish inaugurated a foundation that has since financed the funerals of over 150,000 Canadian soldiers across the country [4].

In about 1925 the church was sold to Montréal's Syrian Catholic community who renamed it Saint-Sauveur. However, in 1995 they abandoned the church – presumably to move into their new church in the suburb of Laval 16 miles north-west of the City centre. Meanwhile, Saint-Sauveur's was left to rot.

In 2005, the University of Montréal and the Government of Quebec decided to build a new mega-hospital to replace the three hospitals that the University runs [5]. When it became known that its construction would require the demolition of the church, the President of Heritage Montréal, Dinu Bumbaru, vigourously protested. After much negotiation, a compromise was reached by which it was agreed that the demolition would go ahead but the hospital authorities would incorporate a replica of the church steeple in the plans of the hospital [3].

The church was duly demolished and there's a pretty full record of that operation at Vanishing Montréal Magazine. When I took my photograph in June 2015, both hospital and replica steeple were in the course of construction as it has been the some time. Phillippe Du Berger is photographing the stages of the process starting at here.

The dedication Trinity as applied to Anglican churches in Montréal can be traced back to 1840 when a Trinity Church was built in St Paul Street opposite Bonsecours market. In 1860 the congregation moved to Gosforth Street and in 1865 it moved again, this time to the church the corner of Viger and St Denis that became Saint Sauveur. The reason that the church was sold to the Syrian Catholic community was that, in 1922, work had begun on the construction of a new church at 5220 Sherbrooke Street West. That church is Trinity Memorial and, in the tradition of its antecedents, it has a military connection in that commemorated the soldiers who died in World War I. The church is still actively serving members of the Anglican community in Montréal [6].

The church that became Saint Sauveur was not the only church dating from 1865 that was to take the name Trinity. In that year Sherbrooke Street Methodist Church was also built to the design of The British-born Cyrus Pole Thomas (1833-1911), an architect who, with his son William, designed a number of buildings in Montréal. At about the same time as the Trinity congregation was moving to their Sherbrooke Street church, the Methodists sold their church to the Greek Orthodox community who renamed it Holy Trinity Church [7].

References

[1] Ulysses Travel Guide Montreal, 2006 p110,

[2] Biographical Dictionary of Architects in Canada, 1800-1950

[3] 1851 English census return.

[4] Radio Canada, 24 November 2010.

[5] Wikipédia français.

[6] History of Trinity

[7] Montréal Gazette, 8 March 2011; Montreal's Architects.

The last edifice of interest we saw before returning to the ship for lunch was one of the four gates to Montreal's Chinatown. This one is at the junction of Viger Avenue East and St Lawrence Boulevard.

Chinatown beyond is located South of Rue Sainte Catherine and North of the Vieaux-Montréal. It was once home to the the City's Jewish community:

One of the four gates to Montréal's Chinatown

In spite of a dismal forecast, as can be seen from the sky beyond the Chinatown gate, as can be seen it was fine when the photograph was taken. In fact it had been like that for most of the morning. However as we set out after lunch to visit the south-west part of the city, though it was still dry, the sky looked somewhat foreboding.

Nevertheless, we took a shortcut to Place d'Youville, and thereby to rue McGill. Had we any sense we would have made a beeline for the Cathedral of Mary, Queen of the World, before it rained. Instead we dallied in Victoria Square:

Victoria Square

Then we admired the Bell Telephone Building and visited the Place Bonaventure, a huge shopping mall that incorporates Central Station. There we purchased a bottle of Benylin cough mixture as we both had the notorious "Black Watch cough". Fellow passengers say it's down to the air conditioning on the ship. As we emerged from the mall, the rain was coming down in torrents and, by the time we got back to the ship, we were soaked.

Édifice Bell

Were we wrong to admire the Bell Telephone Building? It's very much of its time and, as skyscrapers go, it's unpretentious and has a modicum of style. It was designed by the firm of Barott and Blackader and completed in 1927.

Both Ernest Isbell Barott (1884-1966) and Gordon Home Blackader (1885-1916) came from families of architects. Captain Blackader was seriously at Ypres in June 1916 and died from his wounds in London in August the same year. Barott decided to retain the name of his late partner in the title of the practice, and the name 'Barott & Blackader' continued to be used until 1953. The Blackader-Lauterman Library at McGill University is named in memory of Gordon Blackader and now houses one of the outstanding collections of architectural books and journals in Canada.

The firm was responsible for many buildings in Montréal including Edifice Aldred and Théâtre Saint-Denis. But perhaps their grandest building that they were involved with was Montreal’s Canadian Pacific Railway Station:

Gare Windsor (Skeezix1000, Wikimedia)

The station was designed in the late 1880s by Bruce Price, who has already featured in this blog as the architect of the Jacques Viger Building. In association with Daniel Webster and Walter Painter, Barott and Blackader were commissioned to incorporate extensive modifications into the building in 1910. Over the years the building became known as Gare Windsor but, alas, it's longer a station. Nowadays it houses offices, restaurants and a hotel.

To this day I'm fretting that we didn't cross to the other side of Place Bonaventure. Had we done so we would have seen the Cathedral of Mary, Queen of the World. I'll therefore make one call last call on the services of Jean Gagnon for a photograph of that cathedral and also of Christ Church Anglican Cathedral.

The Cathedral of Mary was consecrated in 1894 as Saint James Cathedral, At the time it was the largest church in Quebec. It was made a minor basilica in 1919 by Pope Benedict XV and was rededicated in 1955 to Mary, Queen of the World, by Pope Pius XII.

La cathédrale catholique du Marie-Reine-du-Monde

(Jean Gagnon, Wikipédia)

Christ Church Anglican Cathedral is located at 635 rue Saint-Catherine Street Ouest and is the seat of the Anglican diocese of Montréal. It was designed by Exeter, Devon-born Frank Wills (1822-1856) but, before its construction began, he died and the Montréal architect, Thomas seat and Scott (1826-1895) took responsibility for implementing his design. It was consecrated in 1867:

Christ Church Anglican Cathedral

(Jean Gagnon, Wikimedia)

Originally dedicated to St James, Saint-Jacques’ was Montreal’s first purpose-built cathedral and served as such from 1825 to 1852 when it was destroyed by fire. It was rebuilt to a design by John Ostell but that building burned down a year after it was consecrated in 1857. The present building was designed by Victor Bourgeau and consecrated in 1860. The tall spire was added in 1876. Yet another fire destroyed much of the building in 1933 and its future became uncertain. However, in 1973, what remained of the building including the spire and transept were classified as historic monuments and purchased by Université du Québec à Montréal.

Église Saint-Jacques 1945 (photograph posted to Wikimedia

from the archives of Université du Québec à Montréal)

The Melkite Greek Catholic Eparchy of Saint-Sauveur is thought of as a cathedral by many and, to give credence to the contention, it has a patriarch and a bishop. It's located in the borough of Ahuntsic-Cartierville west of the City:

Cathédrale grecque-melkite Saint-Sauveur

(Stéphane Batigne, Wikipédia)

The Ukrainian Orthodox Cathedral of Saint Sophie is in the borough of Rosemont–La Petite-Patrie north of the City. It dates from 1962 and was designed by Vladimir Sichynsky:

Cathédrale orthodoxe ukrainienne de Sainte-Sophie

(Georgiosiravos, Wikimedia)

Cathédrale orthodoxe Hors Frontières de

Saint-Nicolas (Wikimedia)

The Greek Orthodox Cathedral of St George is at 2455 Cote Ste-Catherine:

Cathédrale Orthodoxe grecque Saint-Georges

(photo © GrandQuebec)

I can't end this account of our visit to Montréal without thanking Jean Gagnon for putting so many fine photographs on the Wikipedia Wikimedia sites.

Jean-Gagnon

Sources used for the Montréal account may be viewed here.

Québec City, the weekend of 6-7 June

The accounts of this weekend and of our visits to the remaining ports of our cruise will have to wait until October 2015.

What's to come in part three?

8 June: Saguenay, Québec

10 June: Havre-St Pierre, Québec

11 June: Corner Brook, Newfoundland

13 June: St. John's, Newfoundland

Unfortunately I have had to abandon this blog until further notice.

For Saguenay to Southampton go to Part III

.jpg)

No comments :

Post a Comment